Teaching with Myth: Enter the Labyrinth

Each week, I teach an online mythology and folklore class with kids worldwide. This week, we explore the mythology and symbolism of the labyrinth.

This post is a mix of life-writing, reflection on my chat with kids, and mythological thinking.

Featuring: bull-head boys, disorientation, and commonalities between Minoans and lesbians.

I hope it will be of interest to anyone interested in myth, folktale and the craft of educating.

Crete is a beautiful island. A recent visit to the mythological sites there gave me the chills. I work in the world of myth, legend, folklore and nature, yet I’m a recovering overthinker, too much in my head to always feel what a place is doing to me.

Not so in Crete. I felt the shadows of a divinity I don’t even believe in. I heard echoes of the ancient times resonating off of cave walls.

On Crete, I am working with the anthropologist and ethnomusicologist, Professor Dr Maria Hnaraki. We are developing a mythology retreat for children, which we will co-facilitate from 2025.

We will take the children to Mount Ida, to the Cave of Talos (the metal giant gifted from Zeus), to the cliffs from which Icarus and Daedalus leapt, and - of course - to ‘the labyrinth’.

There is a quite profound challenge to that last one. Namely, it doesn’t exist. Kind of…

The Story Guild Lesson

This week, I launched my ‘Story Guild’ classes on Outschool. At the time of writing, I’ve taught only one little group of three students. I have ten kids signed up in total now, and that feels like about enough.

They range between 10 and 13 years old - a great age to get deeper into mythological thinking.

This session was titled ‘The Real Story of the Minotaur and the Labyrinth’.

In this post, I’ll take each part of the lesson I taught with the children, and expand it out. I’ll share our chatter.

What do we know about the Minotaur?

all child names are changed

In Greek mythology, the Minotaur was born of the unholy union between the goddess Pasiphaë (daughter of the sun, Helios), and a very attractive white bull. This was a typically misogynistic way of punishing Pasiphaë’s husband, King Minos.

King Minos wished to show that he was the rightful chosen heir of the throne in Crete. He sought a blessing from Poseidon. The god of the seas sent down a magnificent white bull, to show that Minos had his favour. This was done in the explicit expectation that Minos would then sacrifice the bull back to Poseidon, restoring the balance.

But King Minos, being a wrong’un, tried to trick Poseidon by keeping the original, and sacrificing a substitute. Poseidon got mad… hence his mindtricks led Pasiphaë to desire the bull.

…

When I’m teaching Greek mythology with young children, I face many ethical dilemmas almost every lesson. How to reconcile the fact that Greek myths are seen as part of the canon of classical children’s literature with the fact that so many document sexual violence, incest and abject gore?

I try to strike a balance between being ‘age-appropriate’, and also not letting things pass that need to be commented on. If I am talking about Zeus ‘kidnapping’ Europa, I need the children to understand that this in itself is a barbaric thing to do.

I teach myth humorously, but again, it is a balance I need to maintain carefully. I use humour to engage their interest and to keep a critical voice in my storytelling. I don’t want the humour to trivialise or normalise all aspects of the myths…

…

The children shared what they know of The Minotaur. They knew the story of his parentage and they knew the most famous aspects of his story.

They knew that the monster was trapped in a maze and that people were sent from another city (Athens) to kill the beast.

I then prompted them with a question, as I anticipated the children using the word ‘monster’ when I was designing the lesson.

This question is one I really like to pose to children when we are talking about mythology.

Very often, the ‘children’s versions’ of mythological stories remove the nuance of complex characters. Partly, this is often because the nuance involves bestiality (The Minotaur), sexual violence (Medusa) and other events that don’t need to be shared on Zoom mythology lessons between me and some distant 10 year olds.

But when Medusa becomes just ‘an ugly monster’ and the Minotaur becomes ‘a murderous angry beast’, we deprive children of the chance to seek out complexity.

When I asked them what makes a monster a monster, their responses began by pointing out physical features - the red eyes and the horns are what makes it a monster. I point out the illustration on the left, where the Minotaur looks curious and quite child-like. Is it still a monster?

Robert- What makes a monster a monster is its personality.

Me - Interesting. So everyone, do you think that the Minotaur is a monster?

Max - … I mean… yeah. It was bloodthirsty in the beginning.

Me - And does it need to be bloodthirsty all of the time to be a monster? … (quiet thinking moment) What do you think Kai?

Kai - If it’s bloodthirsty half the time and kills someone, then comes back to its good side … then it still killed that person. So it still has to go to jail.

I went on to explain a little more about how with all mythological and folk tales, we can think of our process of telling the stories as using different lenses.

Kai’s point is an interesting one to me. That idea of ‘go to jail’ feels very final in the mind of a child - it is an endpoint.

It is interesting to maybe think about the differences and similarities between a labyrinth and a jail - in their physical senses as well as metaphorical.

Telling the story of King Minos

We acted out a story that I had written on screen with annotated comic-style illustrations. This is the style of storytelling I use most often when storytelling online.

They become an equal part of the telling, taking on characters as much as they want.

If you’re keen to see what this looks like in action, I taught this part of a lesson live on Youtube and Instagram for the Outschool community, with three other students.

All about the amazing island of Crete

It is fascinating how many of the core tales within the Ancient Greek mythos have their origins on this island.

I talked to the children about Knossos, the palace of the fabled King Minos. Or not fabled… real. Or semi-fabled.

This is where the world of myth meets archaeology meets history, and it can get a little murky. Let’s talk about Labyrinth.

The Labyrinth

In the classical myth, King Minos was faced with the dilemma of his rapidly-growing and increasingly-hungry monstrous child. The child’s name, Asterion, is forgotten to most - he has become ‘Minotaur’ (Minos+taurus = Minos’s bull).

An inventor washes up on Crete along with his son. He announces himself as Daedalus. Often seen as the Wise Parent Good Guy archetype, it is worth noting that Daedalus was seeking refuge in Crete because he hurled his nephew from a tower back on the mainland, in a fit of envy.

Anyway.

King Minos offered safety to Daedalus and Icarus, if the inventor would help him to solve his Minotaur problem. And so Daedalus designed the labyrinth, an intricate maze structure.

Pop the Minotaur inside to roam around in semi-lost confusion! Pop a few Athenians in there for mid-morning snacks! Lovely stuff.

What did the ancients think of the ancients?

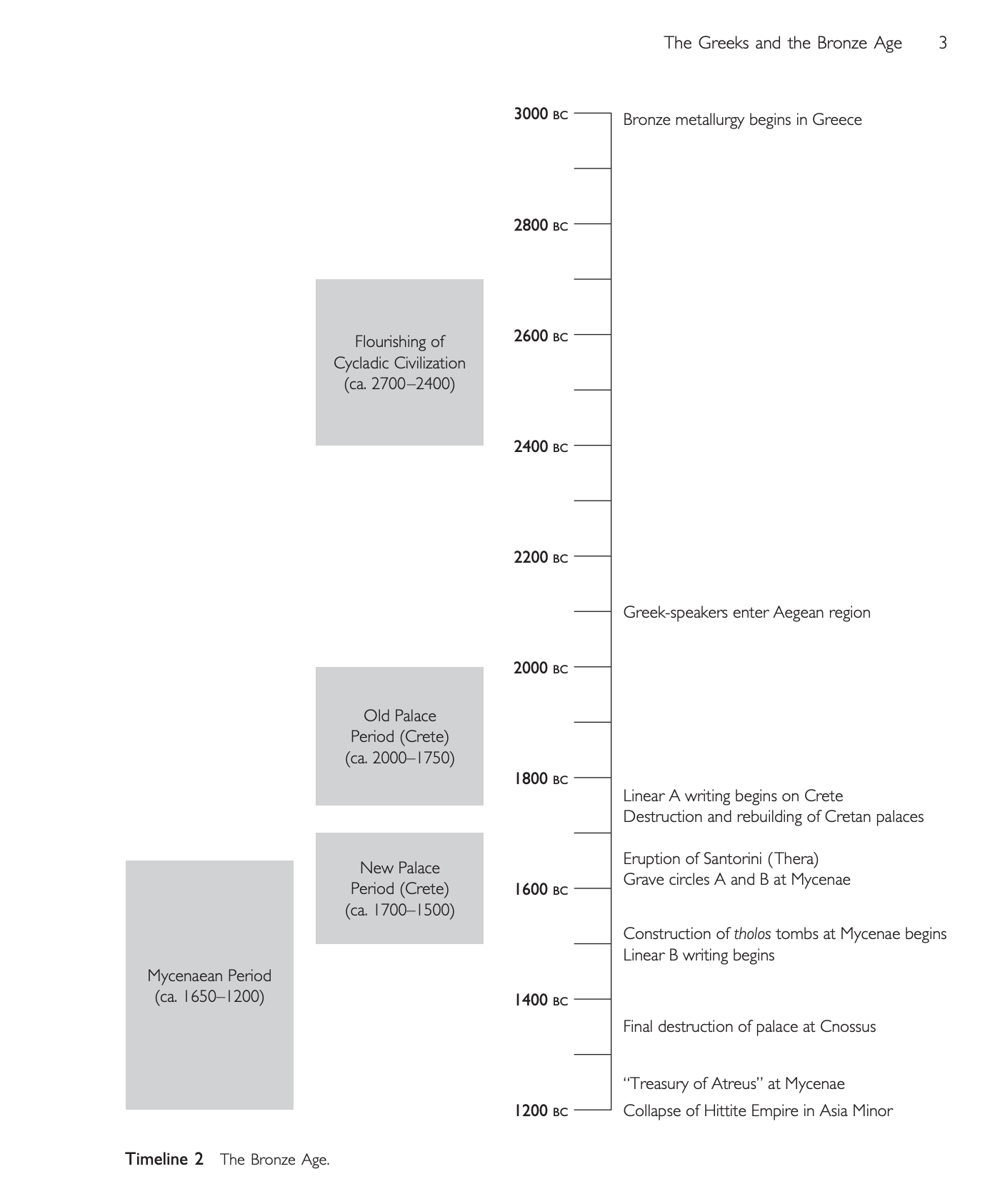

Here’s an important thing to remember. When we are talking about the ‘Ancient Greek times’, if we choose to take the first evidence of bronze metallurgy as a starting point, we are talking about roughly 3,000 years of history, from around 3000 BCE

This means that we today - in 2025 - are living closer in time to the Hellenistic period of Alexander the Great, than the time Alexander the Great himself was living compared to the start of the Greek bronze age!

What’s the significance? Well a great deal of the myth-telling of the Ancient Greeks that survives today comes from these later periods, and from the Romans. Ovid etc.

When talking about this with the kids, I distinguished - confusingly - between the really ancient ancients, and the less ancient ancients.

Now to complicate things further, Knossos itself, on Crete, has been inhabited going back to c. 7000 BCE, to the Neolithic period.

And the Palace of Knossos was built around 1700 BCE and had already been destroyed by 1350 BCE - it’s been buried or in ruin for over three thousand years.

Recent archaeology unearthed many wonders, but not the labyrinth as described in myth. Why might that be?

The labyrinth did not ever exist - it was just part of an invented story about bull-head man

The labyrinth has not yet been discovered

The labyrinth is The Palace of Knossos

Labyrinth as Metaphor?

Whilst it is disputed, the etymology and morphology of the word labyrinth itself points to Knossos. A root of ‘labyrinth’ is ‘labrys’, meaning ‘double-headed axe’, making labyrinth ‘palace of the double-axe’.

The labrys is and was a fascinating symbol of power: associated with female deities in the Minoan period in Crete, and adopted by the lesbian power movement since the 1970s. More about that flag’s contested history here.

Throughout the ruins of Knossos, you can find countless small carvings of the labrys, and with it being an important meeting place in a time in which the labrys was an important symbol of important female deities… it makes a good case for the labyrinth being tightly linked to Knossos.

But then… where’s the maze?!

One interesting idea is that Knossos itself is the labyrinth.

If we take the meaning of labyrinth in its modern senses, literal and metaphorical, it is interesting to apply that to Knossos itself.

a place constructed of or full of intricate passageways and blind alleys

something extremely complex or tortuous in structure, arrangement, or character

The design and floorplan of Knossos is certainly ‘labyrinthine’. When I showed this slide below to the children, I asked them to consider the similarities and differences between the ‘classical labyrinth’ we know from myth (left) and the floorplan (right).

Me - The idea of the labyrinth in the myth was to use confusion as a kind of prison. To use confusion as the tool to control the Minotaur. On the left we have a real labyrinth. The thing on the right is not a labyrinth. It’s the floorplan of the real palace at Knossos. Do you notice any similarities between the palace and the labyrinth?

Kai - The picture on the left has a hole in the middle, and so does the picture on the right.

Me - Good so we have that green section with no walls and the same in Knossos. Good. Any others you notice?

Kai - Er… there’s are also many lines in both mazes that look designed to confuse you.

Me - Good, yes. Max?

Max - Only a couple of entrances and exits to keep you lost in there.

Perhaps, then, the mythical story of the maze was simply laid over the architectural reality of Knossos. For strangers visiting this incredibly disorienting palace, with shifting doors and walls, five stories, and circuitous routes, they found themselves in a state of awe, delirium and lostness.

As they found themselves stuck in the place between where they were and where they wanted to be, they lingered in this liminal space - a show of power as well as enchantment.

Perhaps later Greeks found only the ruins of Knossos and, seeing the complicated patterns of stone, they perceived a labyrinth when what was there was a ‘labyrinthine’ palace.

Tell me when you feel like you’re being trapped?

Possibly right now, trapped in the social expectation of finishing reading my blog?

Here - you have earned a musical reward.

This is the music to accompany Professor Maria Hnaraki’s book about the Labyrinth.

width="100%" height="352" frameBorder="0" allowfullscreen="" allow="autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; fullscreen; picture-in-picture" loading="lazy"></iframe>

For me, I felt like researching this lesson and thinking more analytically about the labyrinth as a metaphor really helped me to put words to how I felt in Knossos.

I was being led by an expert-guide, who walked the uncertain steps with confidence. I was bamboozled - my awe flying off in different directions, genuinely becoming lost. Surprised to see myself lookup at the columns, having not realised I had descended. Losing track of where I was.

Something in the relationship of the tour guide and tourist had traces of how - perhaps - the local traders might have felt, as compared to someone freshly arrived, blindsided in amazement and disoriented.

If Knossos is the labyrinth, it makes me think of what else is.

I think of when I got lost in Chandni Chowk in New Delhi, on my first day in the city…

We can also use the labyrinth as a metaphor for our own minds - for those unseen passageways that lead us to places unknown, that disorient us by design.

What about you?

What do these questions get you thinking?

References:

Beyond the Binary: Gender, Sexuality, Power - Pitt Rivers Museum, Oxford

Insides, outsides and the labyrinth: Knossos, palatial space and environmental perception in Minoan Crete (2023) (open access) - Vesa-Pekka Herva & Jonas Rapakko, Department of Archaeology, University of Oulu, Oulu, Finland

The Minoan Double Axe Symbol: Origins, Archaeological Evidence, and Religious Context - Dimosthenis Vasiloudis (The Archaeologist.org)

Maybe we don’t always let children get as ‘lost’ in something as we should. Too much is too tightly controlled. Children are often told what they ‘should’ find, but if they looked more freely then I reckon they would all find something a bit different.